The Mirage of America's Special Sauce Theory

On June 27, a policeman killed a 17-year-old French kid of Algerian and Moroccan descent near Paris, which set off a week of riots everywhere in France. Although we don’t have good data on the people who were involved in the riots, it’s widely accepted that the overwhelming majority were descendants of North-African and African immigrants. While people generally don’t dispute this fact, which is obvious to anyone who has watched the videos of the riots, many nevertheless insist that the riots had nothing to do with immigration on the grounds that the vast majority of the rioters were born in France and have French citizenship. This is obviously sophistry, but this argument is absolutely ubiquitous, not just in France but also in the foreign press. For instance, shortly after the riots started to calm down, The Economist published a piece that contained this passage:

The far right blames the rioting on immigration and, said Marine Le Pen, a “problem of police authority”. ... No matter that Nahel was a French citizen, who grew up in France. Nor that less than one in ten of those arrested for violence or looting was foreign.

According to this argument, if immigrants come to France and have kids who riots, this has nothing to do with immigration because the kids in question were born in France and therefore are not immigrants themselves.

As far as I can tell, the implicit premise in that argument seems to be that, unless something is a sufficient condition of a phenomenon, it can’t be a cause of that phenomenon. But this is obviously false, since no cause is ever a sufficient condition of its effect. The existence of a causal relationship always requires that some background conditions obtain. It doesn’t have to be any particular set of background conditions, often any one of a number of them will do, but the cause is almost never a sufficient condition on its own. For instance, nobody would object to the claim that Cortés’s expedition to Mexico caused the downfall of the Aztec Empire, but it clearly wasn’t a sufficient condition for that outcome and indeed the Aztec Empire would not have collapsed if a number of other things, such as the decision by Aztec vassals to side with the Spaniards or the epidemic of smallpox that decimated Tenochtitlan after Cortés was forced to flee the city, had not also taken place. While those are the background conditions that actually made it possible for Cortés to destroy the Aztec Empire, his expedition could also have produced that outcome if a number of other things had happened. The fact that a cause doesn’t have to be sufficient condition for its effect is so uncontroversial in the philosophical literature on causation that it was seen as a major flaw in John Stuart Mill’s theory of causation, which motivated John Leslie Mackie’s to propose that a cause be conceived as an insufficient but necessary part of an unnecessary but sufficient condition for its effect.1

This argument is obviously fallacious and, for the most part, people who say that are just trying to wish away a truth they deem inconvenient. To be clear, I’m not saying they are being dishonest, I think they genuinely believe the argument to be sound because they’re conceptually confused about causation. It’s just that, if they didn’t find the causal relationship in question unpalatable, they wouldn’t make that argument. I wouldn’t have bothered writing about this argument if I didn’t think that people were getting at something more interesting when they say that, but I think they are, even if they’re confused and as a result make that fallacious argument instead or in addition to the more interesting claim they’re getting at. The claim in question is that, although immigration obviously has a lot to do with the riots (since most of the rioters were children of immigrants and wouldn’t have lived in France if not for immigration), immigration wouldn’t have resulted in such widespread civil unrest if French society were not flawed in a way that created the conditions for that. In particular, according to that line of argument, immigration wouldn’t result in riots if France were not plagued by systemic racism. Ultimately I also find that claim unconvincing, but unlike the argument that immigration has nothing to do with the riots, it’s at least not obviously fallacious.

I don’t intend to refute this claim here though, but only a common argument that people make in support of it. The argument is that, since the US also has a lot of immigrants but does a much better job at integrating them than Europe in general and France in particular, something about how Europeans deal with immigration must be wrong and it wouldn’t result in problems like widespread rioting if we took a page from the American playbook on that issue. In other words, America has a special sauce about immigration that results in better outcomes and explains why immigrants are better integrated in the US than in Europe, so I will call that hypothesis “America’s Special Sauce Theory”. The claim that immigrants are better integrated in the US than Europe would deserve to be nuanced, but even if I think that Americans exaggerate the extent to which it’s true, I don’t deny that it is and will therefore not dispute it. However, America’s Special Sauce Theory rests on a much stronger claim, namely that the US is better at integrating immigrants than Europe other things being equal and that it’s why immigrants tend to do better in the US than in Europe.2 Although most proponents of America’s Special Sauce Theory don’t seem to realize that, in order to establish that claim, it’s not enough to show that immigrants in the US are better integrated than in Europe. Indeed, even if the US is better than Europe at integrating immigrants other things being equal (which may be true to some extent and that in any case I will concede for the sake of the argument), things are very much not equal.

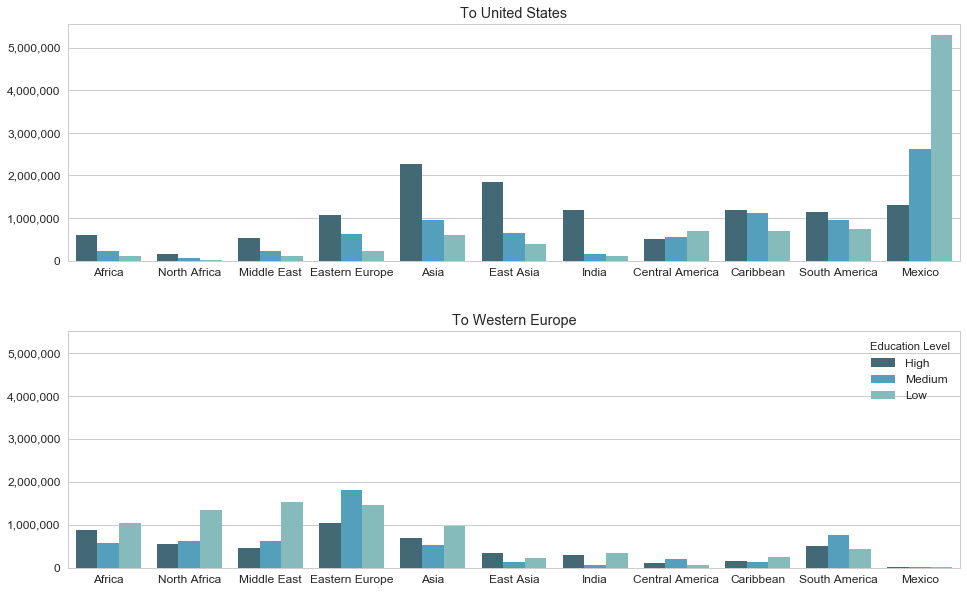

Indeed, the immigrants Europe has to integrate are not the same as the immigrants the US has to integrate, they tend to come from different countries and have very different characteristics. For instance, here is a chart showing immigrants in the US and Europe broken down by region of origin and education level in 2010 (it was made by Jonathan Pallesen based on the IAB Brain Drain dataset), which illustrates that very clearly:

The education level are less than high school (low), high school (medium) and high (more than high school). As you can see, not only do immigrants in the US come from different regions than immigrants in Europe, but except for Mexican immigrants they tend to be much better educated.

Given that immigrants in the US are so different from immigrants in Europe, it makes no sense to assume that, if the former tend to fare better than the latter and don’t create the same kinds of problems, it’s primarily because the US is better than Europe at integrating immigrants other things being equal. I have already conceded that it may true to some extent, but even if it is, the differences between the kind of people who emigrate to the US and those who emigrate to Europe could still be doing most of the work. Proponents of America’s Special Sauce Theory, however, completely ignore the fact that Europe and the US don’t have the same immigrants and think that America’s “special sauce” is the only reason why immigrants are better integrated in the US than in Europe. When you point that immigrants in the US are very different from immigrants in Europe, as I recently did, proponents of America’s Special Sauce Theory invariably bring up the case of Mexican immigrants in the US and make a variation of this argument:

The argument is that, since the vast majority of Mexican immigrants in the US have received little formal education and still do okay, the fact that Muslim immigrants are well-integrated in the US but not in Europe can’t be because they tend to be highly-educated in the US but poorly educated in Europe. I’ve heard variations of this argument, which I call the Argument Ad Mexicanos, countless times over the years, but it’s obviously fallacious.

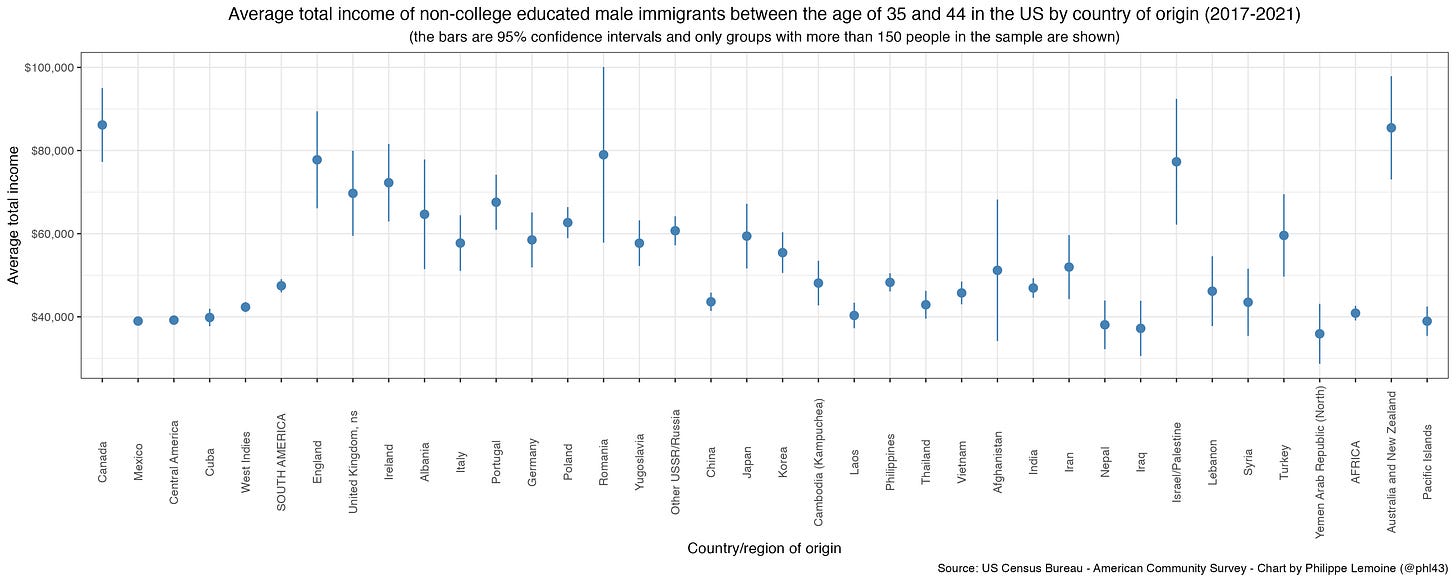

The problem with this argument is that it implicitly rests on the assumption that, once you control for education and perhaps a handful of other socio-economic variables, different ethnic groups are just as easy or hard to integrate, but nobody who is even remotely familiar with the data can find that assumption plausible. Indeed, on just about every metric that is relevant to how well-integrated immigrants are, a huge amount of variation remains associated with the country of origin even when you control for education. For instance, even if you look only at non-college educated immigrants in the US and in addition control for age and sex, the average personal income still varies wildly depending on the country of origin:

As you can see, even though in addition to restricting the sample to non-college educated immigrants I also eliminated the most obvious sources of confounding by looking only at men between the age of 35 and 44, there is still a lot of variation associated with country of origin.3

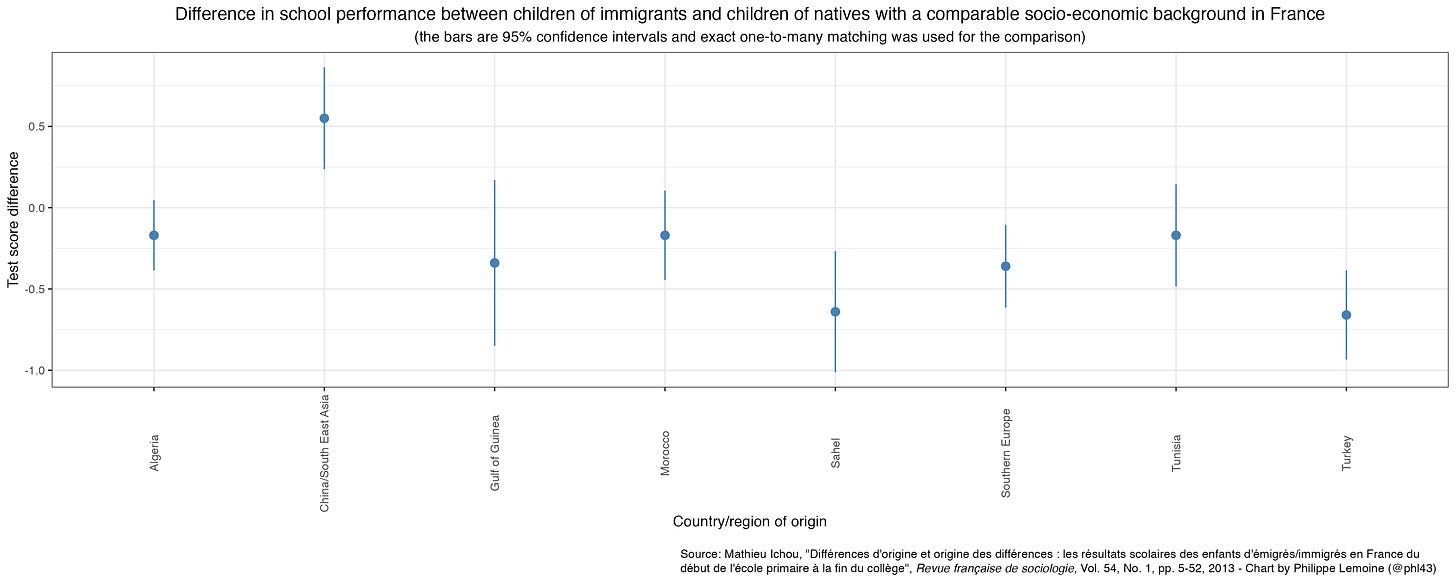

For another example, we can look at French data on how the children of immigrants do in school, which also show that a lot of variation in performance remains associated with country of origin even when you control for socioeconomic background. This chart shows the difference between standardized test scores obtained by children of immigrants and children of natives matched on various socioeconomic variables in a panel of 15-year old students in France:

As you can see, even though the paper I used to make this chart used many variables besides parental education to compare children of immigrants to children of natives with a similar socioeconomic background, a large amount of variation remains associated with the region of origin.4 In some cases, the difference in standardized test scores between groups exceeds one standard deviation, which is very large.5

I could go on like that for hours, but hopefully you get the idea and, if you don’t, I doubt that multiplying the examples will help. No matter what outcome you examine, whether it’s crime, employment, income or anything else relevant to how well integrated different groups are, there will be large differences between different immigrant groups even if you control for education and a bunch of other things.6 Moreover, comparing different groups of similarly educated immigrants in the same country of destination actually understates how much similarly educated immigrants in different countries of destination differ in ways that affect how easy they are to integrate, which is what matters for the Argument Ad Mexicanos. Indeed, immigrants are not randomly drawn from their country of origin but selected in various ways and they are selected differently in different countries of destination, hence similarly educated immigrants in the same country of destination are more similar than across different countries of destination. In fact, since immigrants are not just selected differently in different countries of destination with respect to observed characteristics (such as education), but also with respect to unobserved characteristics (such as intelligence), even similarly educated immigrants from the same country of origin in different countries of destination will differ in ways that affect how easy they are to integrate. In particular, because it’s much harder to move to the US from Africa or the Middle East than to Europe and the kind of resourcefulness it takes to pull it off probably makes you more likely to integrate, it’s likely that even non-college educated immigrants from Africa and the Middle East in the US are easier to integrate than similarly educated immigrants from the same regions in Europe.

Thus, from the fact that the US has been able to integrate a large number of non-college educated Mexicans relatively well, one can’t infer anything about America’s relative ability to integrate immigrants other things being equal, because non-college educated Mexican immigrants could still be much easier to integrate than the similarly uneducated immigrants from North Africa, the Middle East and Africa that European countries have such a hard time to integrate and indeed I have no doubt they are. This is a very simple and obviously correct point, but proponents of America’s Special Sauce Theory evidently don’t understand it, otherwise they would not make the Argument Ad Mexicanos. In fact, Europe has no problem integrating some non-college educated immigrants from other parts of the world and their descendants, so clearly education is not the only relevant variable. Conversely, the US also has a racialized underclass that is very persistent despite the fact that huge efforts have been made to solve the problem, just as France has spent billions of euros over the last few decades to promote the integration of North African immigrants and their descendants with little to show for it. Even if the US really has a “special sauce” that makes it better than Europe at integrating immigrants other things being equal, since it evidently didn’t work for African Americans or Native Americans, I don’t see why proponents of America’s Special Sauce Theory are so confident that it’s why immigrants tend to do better in the US than in Europe and not because immigrants who move to Europe tend to be harder to integrate than those who move to the US.7

It’s true that I have not shown that, only that the Argument Ad Mexicanos was fallacious, which is not the same thing. But there are several reasons to think that immigrants in Europe tend to be harder to integrate than similarly educated immigrants in the US. First, as I have already noted, distance can be expected to result in positive selection even when keeping the education level fixed. This doesn’t apply to immigrants who move to the US from Mexico, which shares a large border with the US, but even non-college educated Mexicans are culturally much closer to Americans than similarly educated Africans, North Africans and Middle Easterners are to Europeans and this makes their integration easier in a variety of ways. For instance, religion is a powerful barrier to intermarriage, which in turn is a major factor of integration. But the best reason to believe that immigrants in Europe tend to be harder to integrate than similarly educated immigrants in the US may be that America’s Special Sauce Theory, the alternative explanation for the relative failure of European countries to integrate immigrants, isn’t supported by much evidence and actually isn’t very plausible in light of the evidence that is available. Again, it may be true that the US is better than Europe at integrating immigrants other things being equal, but the view that it’s the main reason for the fact that immigrants tend to do better in the US than in Europe is a much stronger claim and it doesn’t pass a basic smell test.

As we have seen, immigrants in the US tend to come from different countries and to be more educated than immigrants in Europe, which alone could easily account for most of the difference in outcomes. Again, the kind of immigrants that Europeans struggle to integrate aren’t present in the US except in insignificant numbers, so the kind of direct comparison that could settle the issue simply isn’t possible. When the same immigrants — at least judging from their observed characteristics — move to Europe, they seem to do just as well relative to the rest of the population as in the US. For instance, East Asian immigrants do very well in the US, but the same thing is true in France, where they have children who outperform the children of natives at school, marry with members of the majority population at rates vastly higher than in the US, etc. The alleged deficiencies of French society that proponents of America’s Special Sauce Theory like to bring up to explain why France has such a hard time with immigration somehow doesn’t seem to affect them. Similarly, Indians are successful in the US, but they also do great in the UK or in Denmark, where they are economically successful, have very low crime rates, etc. It could be that, if the same kind of North Africans, Middle Easterners and Africans who live in Europe moved to the US, they would also do well over there (unlike in Europe), but I don’t see why anyone would make that assumption and in any case we don’t know that since the US either has very few of those people or they tend to be highly educated.8

I guess that, even though the US has no experience with the kind of immigrants that European countries struggle to integrate, proponents of America’s Special Sauce Theory could still be justified to believe that if they had identified mechanisms, whose existence and effects are demonstrated by solid evidence, that makes the US much better at integrating precisely the immigrants that are particularly hard to integrate. However, although they clearly don’t realize that, they have not. To be sure, they confidently put forward various hypotheses about what America’s “special sauce” might consist in, but even when the mechanisms they posit are somewhat plausible, they probably don’t explain much and more often than not the mechanisms in question are totally implausible. For instance, it’s plausible for theoretical reasons that a more flexible labor market facilitates the integration of unskilled immigrants on the labor market and there is even some evidence that it does, but that evidence is much weaker and more ambiguous than people realize and, even if we take at face value the effect sizes in the studies whose results are consistent with that hypothesis, they are nowhere large enough to support the notion that it could explain more than a small part of the huge gaps in labor market outcomes that exist in Europe between some immigrant groups and the rest of the population.9

The evidence that labor market institutions could explain a large share of the absolutely enormous disparities in criminal behavior that exist between some ethnic groups and the rest of the population in Europe, a hypothesis that rests on a more indirect mechanism that for labor market outcomes, is even more elusive.10 As for the other hypotheses that proponents of America’s Special Sauce Theory like to bring up to explain disparities in criminal behavior, not just in Europe but also in the US, they can be rejected with a high degree of confidence. For instance, many people blame the high crime rates of some ethnic groups, such as Muslim immigrants and their descendants, on residential segregation. This hypothesis is not just popular in the US, but also in Europe, where it’s constantly mentioned to explain the high crime rates of some groups. However, if you look at well-designed studies rather than cross-sectional analyses (such as studies that exploit social experiments or high-quality longitudinal datasets), neighborhood effects on crime seem to be non-existent or very small at best. For the most part, bad neighborhood are bad because the people who live in them make them bad, not the other way around.11 Besides, since residential segregation for non-white immigrants is much higher in the US than in France, it’s doubtful that it could explain why, for example, Mexicans in the US don’t commit crimes at several times the rate of natives but Algerians in France do even if neighborhood effects on crime were real.12

In order to explain America’s success at integrating immigrants compared to Europe, proponents of America’s Special Sauce Theory also claim that, because unlike European countries the US was never a nation-state,13 Americans discriminate less against non-whites than Europeans and have less difficulty viewing them as members of the national community. As far as I can tell, when it’s not based on anecdotal evidence,14 this view seems to be based on survey data. For instance, when you look at the share of people in different countries who answered “people of another race” when asked to pick groups they wouldn’t like to have at neighbors, you find that it’s much lower in the US than in Europe in general and in France in particular. However, you can’t really infer anything from that, because there are good reasons to doubt that replies to surveys map onto actual behavior in the same way in different countries. Indeed, while Americans may be much less likely to say they wouldn’t want people of another race as neighbors, residential segregation is much higher in the US than in France and non-whites in France are far more likely to marry white people than in the US. Thus, if this data point shows anything, it’s that social desirability bias is stronger in the US and that Americans are more hypocritical. To be clear, I’m not denying that discrimination against non-whites exists in Europe or even that it contributes to the poor outcomes of some ethnic groups, nor am I saying that discrimination against non-whites is more common in the US.15 It’s just that, to show that differences in attitudes toward non-white immigrants explain America’s success at integrating immigrants, it’s not enough to show that such differences exist.

Indeed, what proponents of America’s Special Sauce Theory don’t understand is that, even if they could show that discrimination against non-whites is more common in Europe than in the US, it wouldn’t establish their hypothesis because discrimination is largely endogenous. As we have seen, immigrants in the US are very different from immigrants in Europe, which alone can be expected to result in differences in attitudes toward non-white immigrants. In particular, I actually would be surprised if Americans were not less prejudiced against Muslim immigrants than Europeans, but I doubt this would still be the case if, instead of receiving a relatively small number of Pakistani engineers, they received millions of Algerians who didn’t even graduate from high school. It’s popular to think that people’s attitudes toward different groups shape reality, but the evidence is that causality mostly runs the other way. To the extent that Europeans discriminate more against non-white immigrants than Americans, I think it’s mostly because non-white immigrants tend to be objectively more problematic in Europe than in the US, which is hardly surprising given how much positively selected immigrants in the US are.16 Again, we also have a lot of East Asian immigrants in France, but they do very well and you don’t hear a lot of them complain about discrimination.17 I just picked a few examples to illustrate the point, but it’s the same thing for everything proponents of America’s Special Sauce Theory like to bring up. There just doesn’t seem to be any plausible mechanisms for what America’s “special sauce” is supposed to consist in and how it’s supposed to produce the kind of massive advantage implied by America’s Special Sauce Theory.

Americans often talk about Europe as if it were one giant country, but it’s actually very diverse and, in particular, European countries deal with immigration and ethnic minorities in a variety of very different ways. For anything that proponents of America’s Special Sauce Theory bring up to explain Europe’s failure at integrating immigrants relative to the US (labor market flexibility, access to citizenship, attitudes toward religion, prevalence of segregation, etc.), there is a lot of variation across European countries, but some groups do very poorly on just about every metric everywhere they are present in significant numbers. For instance, as far as we can tell based on the available data, non-college educated North African immigrants and their descendants have much higher crime rates than the rest of the population and very poor labor market outcomes everywhere in Europe, despite the fact that different European countries have very different immigration policies, political and economic institutions, attitudes toward religion, etc. Conversely, as I already noted, some groups of immigrants do well everywhere in Europe, even when most of them are poorly educated. Again, I could go on for a while like that, but you get the idea. When the same groups have very similar outcomes across very different societies, the rational thing to do is not to blame the poor outcomes of underperforming groups on the alleged flaws of particular societies, even if of course no society is without its deficiencies.

Similarly, I don’t see how it’s rational to posit that America has some kind of “special sauce”, which makes it much better than Europe at integrating immigrants when:

there aren’t plausible mechanisms for America’s alleged far superior ability to integrate immigrants;

the US has no experience dealing with the kinds of immigrants that European countries struggle to integrate;

immigrants in the US tend to be much better educated than immigrants in Europe and are likely positively selected on unobserved characteristics;

the US doesn’t seem to be doing noticeably better and in some cases arguably worse with comparable immigrants;

the US also has a large racialized underclass that is very persistent and suffers from many of the same pathologies as some immigrant groups in Europe.

Again, I’m not to saying that the US is not somewhat better at it than Europe, but the idea that it’s the main explanation for why immigration doesn’t cause the same kinds of problems in the US than in Europe seems to be little more than a purely ad hoc and pro domo hypothesis put forward by people who don’t know much about the issue. The hypothesis that the immigrants who move to Europe tend to be harder to integrate than those who move to the US is more parsimonious and more consistent with the available evidence.18 In other words, it’s geography, stupid.

I think this is clearly true, but if you’re still not convinced I’m happy to retreat to a weaker claim, namely that America’s Special Sauce Theory remains very speculative and isn’t supported by much evidence. In particular, despite how compelling the Argument Ad Mexicanos seems to many, it provides no support for America’s Special Sauce Theory. For this argument to be convincing, we’d have to be able to assume that similarly educated immigrants from different countries of origin are roughly similar with respect to the characteristics that are relevant to how easily they will integrate in Western societies, but we know that it’s not the case. The fact that many otherwise intelligent people clearly have no idea how much variation remains associated with the country of origin even after you control for education and therefore find such an obviously fallacious argument compelling can only be explained by the fact that, when it comes to immigration and a number of related issues, the “marketplace of ideas” is heavily distorted and the intellectual division of labor is not working. Even generally well-informed people are only personally acquainted with the evidence about a handful of topics, because it’s simply impossible to take a close look at the data on every issue. This is generally not a problem because one can usually rely on the intellectual division of labor to learn about topics one hasn’t personally investigated from experts and the media. But on immigration and related issues, this doesn’t work, because nobody likes to be vilified and the people who are familiar with the relevant data are reluctant to say what they show out of fear that it will invite accusations of racism.

Mackie’s theory of causation is widely believed to be inadequate, but for reasons that have nothing to do with his contention that a cause is not a sufficient condition of its effect, which is completely uncontroversial.

For the sake of simplicity, I will talk as if the “integrability” a group of immigrants were a monadic property, but there is no reason to assume that a group of immigrants could not be easier to integrate than another in one society while the reverse is true in another society, so it would make more sense to think of “integrability” as a dyadic property that doesn’t just depend on the intrinsic characteristics of the group of immigrants but also on the country of destination. More generally, the concept of integration is notoriously vague and would deserve a separate discussion, but I don’t think it’s necessary for this post.

The choice of sex and age group I made for this chart was partly arbitrary, but looking at women or different age groups doesn’t affect the conclusion and in some cases even strengthens it. The differences between different groups in this chart should also not be interpreted as reflecting differences between the populations of their respective countries of origin, such as difference in genetics, culture, etc. (though it’s probably part of the story), because as noted below immigrants are not randomly drawn from their country of origin but selected in various ways and there is every reason to believe that, in any country of destination, immigrants from different countries of origin are selected differently because of geography, law, etc. The code for this chart and the next is available in this GitHub repository.

The variables used for the exact matching comparison are father’s education, mother’s education, father’s profession, mother’s profession, employment status of the parents, family structure, child’s gender and the number of siblings. This chart actually understates the amount of variation still associated with the country of origin when you control for those variables because, except for North African countries and Turkey, countries of origin are aggregated in large geographical categories that are probably heterogenous with respect to school performance.

Strictly speaking, this claim doesn’t follow from the results of the analysis on which the chart is based, because they were obtained by comparing children of immigrants from different countries of origins to children of natives and not to each other, but we can nevertheless be confident that it’s approximately true. Also, while many people interpret this kind of results as showing that if we improved access to education for the children from socio-economically deprived families they would get the same test scores as the children from well-off families in the same ethnic group (which if true would mean that one can hope to equalize to a large extent school performance between different ethnic groups by investing enough into anti-poverty programs), one can’t actually make that inference because, even within the same ethnic group, socio-economically deprived and well-off families probably differ in genetic ability.

Even different groups of similarly educated immigrants from the same country of origin are probably very different in some cases, because many countries of origin are very diverse. For instance, I don’t know if good data are available on the socio-economic characteristics of Ahmadi Muslims from Pakistan in the UK, but even when they are poorly educated I wouldn’t assume they’re doing as poorly as similarly educated Sunni Muslims from Pakistan.

When I make this point, proponents of America’s Special Sauce Theory invariably reply that African Americans and Native Americans are not immigrants, but as they like to point out (remember The Economist’s article I quoted at the beginning of this post), neither are most of the people who rioted in France this summer. At bottom, this debate is about the ability to integrate ethnic/racial minorities, not immigrants per se.

Obviously, there are non-college educated North Africans, Middle Easterners and Africans in the US, but in very low proportions compared to their fellow countrymen in Europe. The overall composition of the group matters even for how well-integrated non-college educated members of the community are. Indeed, not only do some problems only appear when a certain scale is reached, but most of the poorly educated members of the community were actually brought through family reunion. Therefore, if the community is dominated by highly educated people, even its poorly educated members are likely to be positively selected on unobserved characteristics, because the family members who made them come are probably well-educated.

A discussion of the literature on the effects of labor market institutions on native-immigrant outcome gaps is beyond the scope of this post, but since people evidently hold very strong beliefs about this issue that are totally unwarranted by the evidence, I would still like to make a few additional remarks about the literature on that issue. First, it consists almost exclusively in cross-sectional studies and there are good reasons to think that confounding is a serious issue, so it’s tricky to make claims about the causal effects of labor market institutions based on that literature. In particular, it’s not implausible that different types of labor market institutions select different kinds of immigrants, in which case the correlations one uncovers would be spurious. The studies in question try to mitigate that concern by controlling for individual-level characteristics, but I think omitted variable bias and measurement error are potentially huge problems in that literature. For instance, according to the data from the Survey of Adult Skills conducted by the OECD as part of the Programme for the International Assessment of Adult Competencies, immigrants and to a lesser extent their children have much lower numeracy and literacy skills than natives with native-born parents even when they are similarly educated. In France or the US, immigrants with a college-degree have numeracy and literacy skills that are similar to those of natives who just finished high school (the disparity would be even larger if we looked at specific groups), so if you just control for the highest degree obtained (which is generally what studies in that literature do), you are going to miss a lot of the relevant variation. Moreover, not only do studies often find that a more flexible labor market is not always better for immigrants and that it depends on the outcome of interest, but they also find inconsistent results. Finally, in the rare cases where they consider the possibility that labor market institutions could have heterogeneous effects on immigrants depending on their country of origin (such as this recent paper), they generally find that it’s the case, which makes it even more difficult to make the kind of generalizations that proponents of America’s Special Sauce Theory routinely do.

I don’t think most proponents of America’s Special Sauce Theory realize how large the disparities in question are. In the case of violent crimes, it’s not uncommon for some groups, always the same, to be arrested at several times the rate of the rest of the population in Europe. For instance, according to the data for 2017 released by the federal police in Germany, Algerians were identified as suspects of violent crimes by the police at about 30 times the rate of Germans. Obviously, a large part of those disparities are the result of differences in demographic composition, but they remain very large even when you account for that. As Inquisitive Bird showed recently, the same thing is true in Denmark, where the data to account for age and sex are also available. As for bias in the criminal justice system, while it no doubt exists, the idea that it can explain more than a small part of such enormous disparities is no more plausible in this case than in the case of the disparity in arrest rates between African Americans and the rest of the population in the US.

This doesn’t mean that segregation doesn’t create problem or even that it’s not bad for integration. For instance, I think there is good evidence that it reduces intermarriage, which I regard as a major factor of integration in the long run and therefore as something that should be promoted. But the idea that segregation explains why some groups commit violent crimes at several times the rate of the rest of the population is absolutely ludicrous.

For various reasons I’m not going to get into here, comparing residential segregation in different countries is tricky, but the difference between France and the US is large enough, even if you look specifically at segregation patterns for non-Western immigrants in France, that I can still confidently make the claim that it’s higher for non-white immigrants in the US than in France.

If you ask me, this claim is disputable or at least would be deserve to be seriously nuanced, but that’s a story for another time.

In many cases, I think it’s not even anecdotal evidence, but straight up myths that have become popular among American liberals. For instance, I can say that what most American liberals believe about how Muslims are treated in France is almost completely disconnected from reality, because the American media are just terrible on that issue and are more interested in promoting a simplistic narrative than in reporting the more complicated truth. I think the problem is that most Americans, even in highly educated circles, have a very poor understanding of European societies. This leads them to interpret some events, such as France’s decision to ban the islamic veil in public schools, in the same way they would in the US, which you can’t because the cultural, political and historical context is completely different. If someone in the US argues that the islamic veils should be banned in public schools, it’s a pretty reliable inference that he is racist in all kinds of ways, but this inference completely fails in France where the prevailing attitude toward religion is very different. This isn’t a defense of the law against the islamic veil in school by the way, I think the whole obsession about that topic is stupid and a distraction from the real issues, but it’s a perfect illustration of how American liberals often draw the wrong conclusions from what is going on in other countries because they’re incredibly provincial and totally clueless about other cultures.

Compared to American liberals, American progressives have the opposite problem and seem to believe that the US is uniquely racist, which I think is just as clueless as the caricature of Europe that many American liberals seem to have in their mind.

Of course, this doesn’t make discrimination fair and it can even compound the problem, if only because even well-integrated people will suffer from it and discrimination can produce frustration that will further discourage the others from making efforts to integrate.

Actually, some of them did complain about discrimination recently, but their complaints were directed at North Africans who attack them in the streets to rob them.

Note that even if America’s Special Sauce Theory were true, it wouldn’t mean that it would be possible to make European societies more like the US in the relevant ways, nor that it would be desirable. Indeed, not only could the relevant differences be the kind of things that can’t easily be changed through policy, but even if they were it could be that trying to do so would make other things worse and that it wouldn’t be worth it on the whole. For instance, as we have seen, proponents of America’s Special Sauce Theory often claim that Europeans discriminate more against Muslims than Americans and are less prone to see them as members of the national community. Now, as I have already argued, I don’t think there is a shred of evidence that such differences in attitudes explain the different outcomes of Muslim immigrants in the US relative to Europe. But even if that were true, it doesn’t mean that it would be easy to fix, because such differences in attitudes, to the extent they exist and are not endogenous to the characteristics of immigrants themselves, are probably very hard to change. It could be that, in the attempt, we’d just end up replicating US civil rights law, which probably wouldn’t change people’s attitudes much and would create far more problems than it would solve if you ask me.

I think the potential for assimilation also explains the attitude of Spaniards towards immigrants. Spain doesn't seem to have much of an "immigrant problem" and most of the Spanish population has a favorable view of immigration, and this might have to do with the composition of the immigrant population in Spain. Close to 40% are Other Europeans (EU and not-EU), close to 30% are Latin Americans and around 9% are Asians.

Other Europeans assimilate just fine, and Latin Americans already speak the language, don't have any religious impediments to intermarriage and assimilation and bring a culture that's not identical but pretty similar. And most Asians come from some of the usual model-minority countries: China, India, Philippines.

So even though immigrants constitute as much as 15% of Spanish population, close to 80% of them belong to the easy to assimilate category.

Interesting, but you seem to dismiss the large gap in the jobless rate between France and the USA. It has always been much easier to get a job in the USA/Canada compared to most of Europe.

https://www.challenges.fr/assets/img/2021/02/18/cover-r4x3w1200-602e64efee6ca-chomage-en-de-la-population-active.jpg